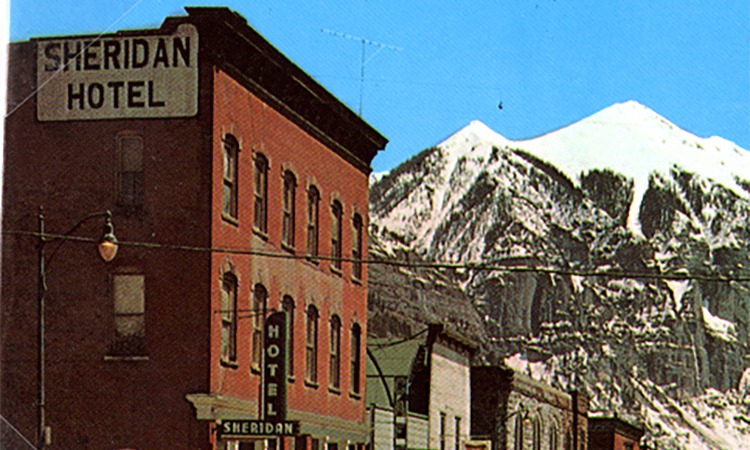

Telluride News

This November, Colorado voters will consider approving and funding the reintroduction of Grey Wolves into Colorado, with the goal of having a self-sustaining Gray Wolf population in the state.

Wolves, of course, are some of the most controversial animals on the planet; old northern European fairytales are rife with frightening lupine references. Wolves remain largely mis-understood. Their packs, hierarchy and behavior continue to be studied. The question is what, if any, are the consequences of a wolf reintroduction plan in Colorado?

In light of its significance, I’d like to evaluate the facts and history and consider what may be the unintended consequences of this vote, if it passes.

Colorado Wildlife has reported regular wolf sightings over the last few years. The wolves seem to be naturally coming back to Colorado.

One case study to consider: some years ago, elk over-population did serious damage to vegetation in Yellowstone National Park. The reintroduction of wolves and/ or the increase of their population appears to have controlled the elk population and its subsequent impact on the vegetation.

In east San Miguel County, we have a lot of elk and therefore elk damage to vegetation. Could the reintroduction of wolves into Colorado and ultimately the San Juans stop this damage to the vegetation and better balance the ecosystem?

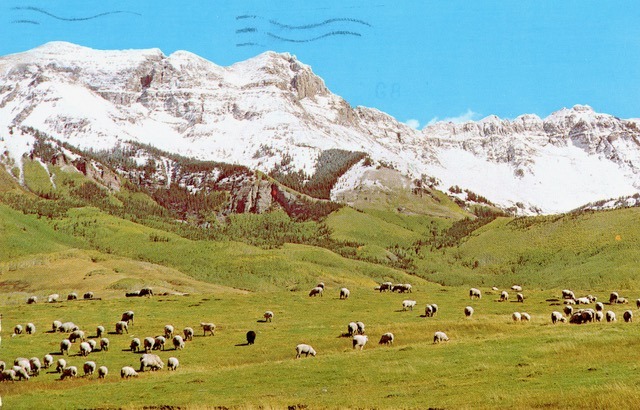

When I moved to Telluride in 1975 elk sightings were few. I consulted Jack Pera, a well-known regional wildlife expert and photographer who owned and operated Timberline Hardware, and asked him where I might spot some of these then elusive animals. In 1990 a wildlife study was done on the elk population on the north side of the San Miguel Valley and Deep Creek Mesa, from above town to Grayhead. In 1990 the elk population was estimated at between 120-150. Fast forward 30 years and that population has increased 10-fold. Why? The reason is simple: few predators and plenty of feed. When the large ranches were in operation—including the Aldasoro Brothers, the Adams and the Alexanders families—they grazed sheep and cattle not only on their substantial holdings but also on all the national forest surrounding their holdings through a permit system. Food was scarce, and high up the mountain, the few elk had to compete with the 5000 plus sheep and hundreds of cattle for food. Alleyoop grazed cattle on the valley floor, thus eliminating food for elk in that location.

That, of course, all changed with the success of the ski area and the subsequent impact of more homes and development. With the approval and inception of several developments Mountain Village, West Meadows, Aldasoro, Lawson Hill etc. a dog prohibition was instituted to counteract the perceived threat to wildlife. Commercial ranching was reduced dramatically, subsequently increasing the feed for deer and elk, causing the elk population to explode. The positive effects are that elk and deer are commonplace and coyotes, bear and mountain lion have become more numerous as well. However, this was an unintended and unexpected consequence of development.

The question that comes logically to mind is: what was it like before the white man showed up and the eco system was supposedly in balance?

Well, we are fortunate because Franklin Rhoda, a member, together with A.D. Wilson (Mount Wilson and Wilson Peak), of the Hayden survey of the territories (then Colorado), kept very good records and Rhoda in his journal made the following entries when describing our area:

“After crossing the canon of the creek above mentioned we came out on a pretty smooth area, covered with scattering timber and fine grass. One thing very peculiar about this particular part of the country is the deathlike stillness that almost oppresses one in passing through it. There is the finest growth of grass I have ever seen in Colorado, with beautiful little groves of pine and quaky asp scattered about, which one would expect to be filled of game. The old trail and the very antiquated appearance of the carvings on the trees, and the absence of all tracks, old or new, indicated that the Indians had abandoned this route long since. With all these conditions, so favorable to animal life, we did not hear a bird twitter in the thickets, and saw neither deer, elk, nor antelope, nor even a single track of one of those animals. In all other parts of the country little squirrels and chipmunks were seen in abundance; but here, if they existed at all, they kept themselves close. We made camp on the large east fork of San Miguel (now the San Miguel itself), just across the stream from station 32 on the map. The next day, September 9, we made station 32, on a low hill on the north side of the creek (on Deep Creek Mesa), which from its width might more properly be called a river (again the San Miguel). Above this for several miles the stream -bed is very flat and covered with willows (the Telluride Valley Floor), while the stream itself winds like a great snake. A short distance below our station the stream plunges down very abruptly into the canon of the San Miguel (Keystone Gorge), which, above and below this junction, cuts down from 800 to 1,000 feet into the sandstone which here makes its appearance. Leaving station 32 on our way to Mount Sneffels, we followed the trail a short distance, and then, turned off to the right, with great difficulty succeeded in descending to the bed of the creek flowing from the northeast (probably Deep Creek). In this vicinity we saw a band of six gray wolves, the first we have seen during the season.”

“Ascent of Mount Sneffels. The weird stillness of high altitudes, only served to heighten the appearance of desolation about us, and gave one the idea that all nature was dead… We reached the pass at last… The claw-marks on the rocks, on either side of the summit of the pass, showed that the grizzly had been before us. We gave up all hope of ever beating the bear climbing mountains. Several times before, when, after terribly difficult and dangerous climbs, we had secretly chuckled over our having outwitted Bruin at last, some of the tribe had suddenly jumped up not far from us and taken to their heels over the loose rocks. Mountain sheep we had beaten in fair competition, but the bear was “one too many for us”.

Rhoda leaves us with this question: was this band of Gray wolves and perhaps others, along with the grizzlies responsible for the lack of wildlife in our area in 1874? Would the reintroduction of wolves decimate the elk, deer and other wildlife? I guess if this November’s ballot initiative is approved, we will leave it to our grandchildren to figure out if this was a prudent move.

Again, the law of unintended consequences could have its effect on wildlife in Telluride, Colorado.

Dirk DePagter